By Larry Gardner, Digifonics, Inc. © 2020

A Bit of History

In the infancy of cinema, silent movies were shot at 10 to 18 frames per second with the speed decided by how fast the cinematographer decided to crank the camera based on the scene being shot. With the advent of sound on film it became necessary to run the camera, sound recorder, and projector at a constant speed. This kept the dialog in-sync and kept the music on-pitch.

One of the biggest expenses in making a movie has always been the cost of the physical film itself, not only during production but for the thousands of prints that were sent to theaters all over the world. Ideally they would use as little of the expensive film as possible. After years of discussions the industry created a standard for movies: 35mm film running at 24 frames per second and with an optical soundtrack. This combination created both acceptable motion rendition and acceptable fidelity in the newly developed optical sound recording systems. So, for 100 years movies have been shot at 24fps, the speed the industry decided was the cheapest way to make films with a level of quality that was acceptable to the ticket-buying public. Yes, the standard was good enough for the public, at least in the late 1920s.

Once the industry agreed on the standard, most 35mm cameras and nearly all 35mm projectors in theaters ran at one speed: 24fps. If you wanted your movie shown, it had to be shown at 24fps. In the 20th Century only a very few films (Mike Todd’s Around the World in Eighty Days, all the Cinerama films) were shot at other frame rates. Also, relatively few were shot on any size film other than 35mm.

Another restriction (mostly based on cost, too) is that virtually all cameras used the simplest mechanism possible which included the 180º shutter angle, so cinematographers were limited to one shutter speed: 1/48 second. Naturally the 16mm filmmaking community embraced the same standards.

24 has been a great speed standard for cinema. In a cool, dark theater, it says MOVIE to your brain and it takes you to a new univese. Obviously, the format has continued to be acceptable and even preferred for many, many years. It defines the cinematic look.

The Age of Electronic Displays

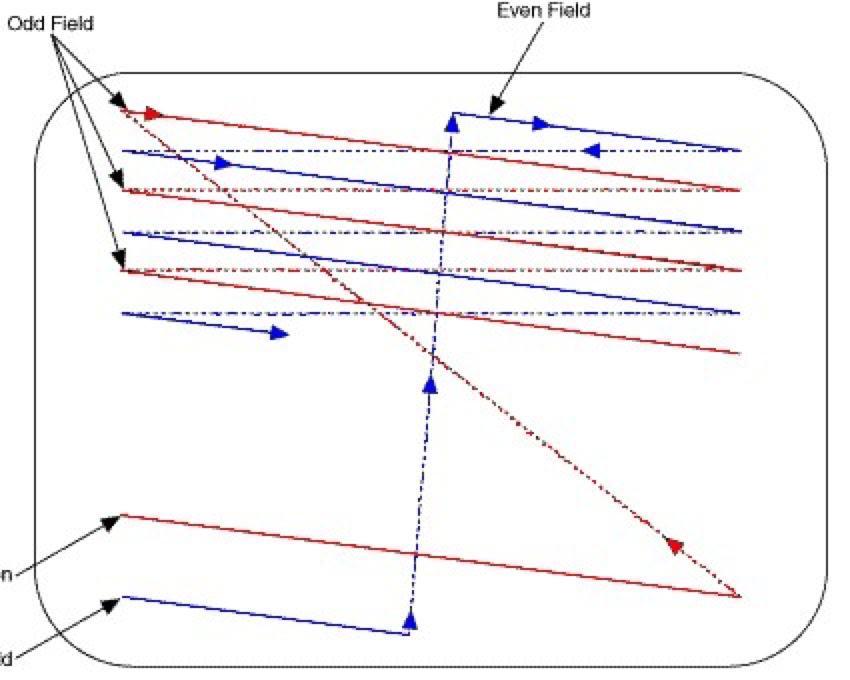

With the arrival of television in the late 1940s, new frame rates appeared. In the US it was 30 frames per second (60 interlaced fields) because of the North American standard 60Hz power line frequency. The original US TV standard had 525 scan lines. The original cathode ray TV tubes displayed the lines starting from the upper left corner and scanning from top to bottom. Interlacing displays half the scan lines (a field) in 1/60 second, offset the image by half a line, then shows the second field with its lines positioned between those of the first field.

How interlace scanning works on a cathode ray tube display.

Interlacing was a great idea at the time because it created 30 full-resolution frames per second but the 60-field display greatly reduced flicker. A film projector reduces flicker in a similar way. Instead of just projecting 24 images a second, it displays each image twice or three times to give flicker rates of 48 or 72Hz. The refresh rate of a display is the number of times per second that the image is re-drawn on the screen, measured in Hertz (Hz) or cycles per second. Today, most displays have refresh rates of 60Hz (or sometimes 50Hz). While TV sets often still use interlaced scanning, most displays today are progressive. They display the lines from top to bottom, one after the other. Because modern displays can work fast enough to prevent flicker, this technique eliminates some artifacts that interlacing can introduce. Still, a progressive display is preferable.

A 1-second repeating animation at 24 frames per second.

Here’s a 1-second 24fps animation that should play at normal speed. You are probably watching it on a display with 60Hz refresh. Notice that the motion isn’t smooth. It’s jerky. That’s because to get 24fps to display properly on a 60Hz display, you have to vary the speed. If you do the math, you can figure out that you need to show one frame twice and the next frame three times to get the 24 frames into a 60Hz refresh. This is called 3:2 pulldown. The irregular motion pattern it produces is called judder. We’ve been looking at this ever since they first put 24fps film on television.

24fps animation at 4% normal speed.

Now here’s a 60fps version of the same animation captured off a 60Hz-refresh screen and played at 4% speed. In slow motion, it’s easy to see what’s happening. The even-numbered frames are shown 1½ times as long as the odd-numbered frames. One-two, one-two-three. One-two, one-two-three.

60fps screen capture of 24fps live action at 4% speed

It’s even easier to see with live action. One-two, one-two-three. One-two, one-two-three.

This problem is all because 60 is not an even multiple of 24. A display with 120Hz refresh can correctly display 24fps footage by showing each frame five times. (120/24=5). That’s the lowest standard refresh rate that works.

Judder gets even worse when you try to integrate 24fps footage into a 30fps production.

60fps screen capture of 24fps animation in 30fps progressive project.

Now we need to add frames to get from 24 to 30, so the easiest way is to repeat every fourth frame. This creates some even worse judder.

24fps animation in 30fps progressive project shown at 4% speed.

Now that you know what to look for, you’ll see this all the time, and you will need innovative software like Twixtor or Optical Flow to correct it.

So it looks like even though 24 fps is an establish standard that everybody uses, there are lots of disadvantages to using it in an world dominiated with 60Hz displays.

Suppose just for a moment that we create our animation (or actually shoot) at 30fps (29.97 really, but don’t worry about that part right now). Here’s an example:

30fps animation captured from a 60Hz refresh screen.

Assuming your computer is playing back correctly and has a 60Hz or greater refresh rate, the motion should be visibly smoother than any previous example. There should be no judder. If you see uneven motion it’s probably because your device is doing something other than the playback. In either case, this will be the best level of accurate motion display your device is capable of.

Notice, too, that there is close to the same amount of motion blur from frame to frame. The amount of motion per frame is 80% of what it would be if we created the animation at 24fps.

The slow-motion version, below, shows the even motion frame to frame that will create the effect of smooth, cinematic motion on the a 60Hz screen.

30fps animation captured from a 60Hz screen displayed at 4% speed.

But what about the Soap Opera Effect? You know, the sickening smooth, silky motion that defines the “Video Look”? If you re-read the part about interlace, you will understand how that look is from using the interlace SIXTY images per second. It does not come from 30fps.

If you want to really simulate the Soap Opera Effect, set your camera for 60 frames per second with a 360º shutter (1/60 second exposure). You’ll get it immediately. Shoot something at 30p (progressive) instead of 24 and set your shutter speed to 1/60 or 1/50) and you’ll see motion rendition that retains the cinematic motion blur and slight flicker on fast motion. There’s only a 20% difference in speed, not the equivalent of running the camera 2.5 times as fast. In other words, running at 30fps does not create the Soap Opera Effect.

What’s really wrong with 24fps is that most displays do not render it correctly. Without synthesizing new frames that didn’t exist in the original footage, it is not possible to display 24fps on a 60Hz refresh display (almost all of them!) .

24fps as a standard shooting speed is a little like the QWERTY keyboard. It’s far from ideal but everyone uses it and nobody wants to change it. Learning a new keyboard may actually be harder than learning a new language. It’s also like using imperial measurements in the US instead of going metric. When you’re used to feet and inches, it’s hard to switch to millimeters and meters. But getting away from 24 is also not like these things, because switching is easy. Only one setting to change.

Oh yes, 24fps is “cinematic” beccause it’s what cinema has always done. It’s easy to forget, however, that until now, cinematographers literally had no choice. Today, when the majority of films are shot digitally and projected digitally, when the cost of film stock is not a consideration, cinematographers suddenly have a choice.

Try 30 fps.

The clips below were shot with a Panasonic GH4. The first clip is “standard” 24fps with 1/50 exposure time (as close to 1/48 as the GH4 gets. The display you are watching this clip on probably has a 60Hz refresh rate, so you will see judder as the cars pass This will be more obvious as the cars pass closer to the camera. On a 50Hz monitor the effect will be worse. Only if you are watching on a monitor with a 72, 96, or 120Hz refresh rate will the footage not exhibit judder while playing.

The other clips are shot at 30fps (30p, not 30i) but with different shutter speeds. None of them should show any judder on a display with 60 or 120Hz refresh rate—that’s almost every phone, tablet, computer, or TV in North America. The clip shot at 1/60 second follows the so-called 180º shutter rule—the shutter speed is the reciprocal of twice the frame rate. Using a 1/50 shutter speed makes the motion blur exactly the same as if it was shot at 24fps following the 180º rule, because the exposure time for each frame is exactly the same.

Classic 24fps 1/50sec exposure,~180º shutter angle

30fps 1/60 sec exposure,~180º shutter angle

30 fps 1/50 sec exposure ~216º shutter angle

Advantages of 24fps:

- If shot on film, compatible with any cinema.

- Uses about 20% less storage space (or film) than 30fps for equivalent image quality.

Disadvantages of 24fps:

- Not fully compatible with any international TV standard (25 or 30fps).

- Not fully compatible with digital displays with lower than 120Hz refresh rate.

- Cannot be converted to standard frame rates without artifacts.

- Will exhibit jerky motion (judder) if played on displays with 30 or 60Hz refresh (vast majority of displays).

Advantages of 30fps:

- Perfectly compatible with digital projection in virtually any cinema worldwide.

- Displays perfectly on 30, 60, 120, 240Hz refresh rates.

- More freedom to choose motion rendition characteristics around optimum shutter speeds.

Disadvantages of 30fps:

- Uses up to 20% more storage space for equivalent image quality.

It’s time to make 30fps the new standard for films and TV.

Author’s notes:

1. For purposes of this page, 23.98fps=24fps, 29.97fps=30fps, 59.94=60.

2. Nothing against our friends in PAL-land where 25 and 50 fps are the standards. They have managed the frame-rate wars far better than we in the world of 29.97fps. Unfortunately, 25 and 50fps can be also be jerky on 60Hz displays, common on computers, tablets and phones.